A while ago I received an interesting e-mail. It was from a gent who was representing a graduate social work program at University of Southern California (USC). Here's what he had to say:

Father of Festus

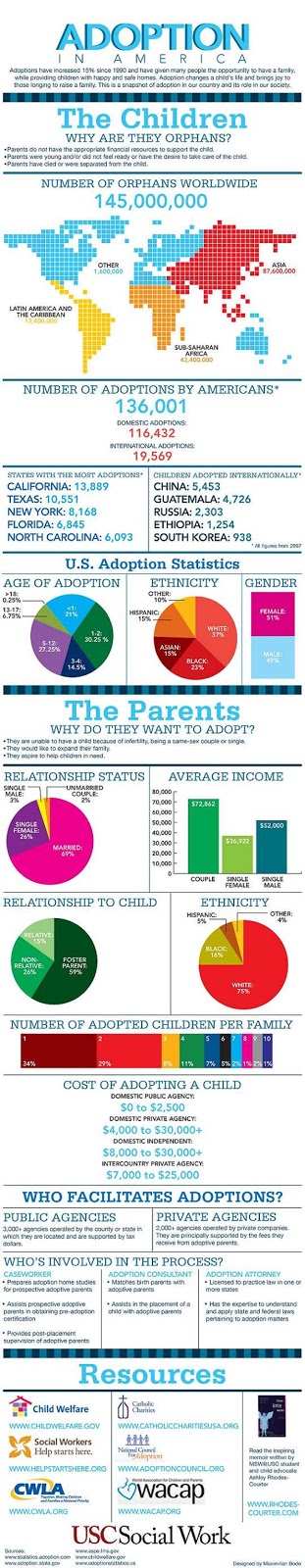

I hope this message finds you well. My name is ******* **** and I work in Community Relations for MSW@USC, the web-based Master of Social Work program at the University Of Southern California. I was reading through your blog Statistically Impossible and found some great posts about your experiences with open adoption. We recently published an inforgraphic, "Adoption in America," and thought it would be a great fit for your site.

http://msw.usc.edu/mswusc-blog/adoption-infographic/

The infographic highlights various details about the adoption process, including those involved; it also contains comparative adoption statistics from other countries around the world. In addition, the graphic provides resources for people hoping to adopt and/or social workers interested in pursuing a career in the field.

Given your connection with adoption, I thought that this infographic would resonate well with your audience and networks! If you'd like to share it on your website, please visit our blog or find the image directly, and also feel free to share this with your social networks via facebook and/or twitter.

If you have any questions or feedback, please feel free to reach out to me, I'd really like to know what you think. I look forward to connecting in the future and sharing ideas.

Thanks,

****

I've removed his name in respect for his privacy. The infographic he referenced was this:

I took a while to chew this over. There were a lot of things that bothered me. In fact I was troubled enough that I didn't consider responding for a couple months. I couldn't bring myself to offer a useful critique. After a while I realized that if I didn't reply my frustration was useless. The information presented would go unchallenged. Yet another opportunity for a first father to communicate directly with those who shape the adoption experience would be lost. I replied thus:

Hello ****,

I'm sorry it's taken me so long to reply to your e-mail regarding the infographic your department put together. Looking at the infographic I've noticed arena's in which the information appears either fuzzy (not specific enough to provide functional data) or is presented in a less than optimal fashion (word choice problems). I hope you'll forgive me for focusing on the negative aspects rather than providing positive reinforcement. The truth is there's a lot of good information here. But I don't want to keep you stuck reading this e-mail. all day. So, on with the feedback:

The infographic preamble is likely to cause some controversy. It is mentioned that adoptions have increased 15% since 1990. What is the cut off for the data? For the sake of clarity it would be good to see that data presented within a spread of a specific perio od time, for example "adoptions have increased 15% from 1990 to 2008". Similarly the discussion of providing children with "happy and safe homes" and "bring[ing] joy to those longing to raise a family" tips the hand to a decidedly positive spin on adoption. If the goal is to promote adoption this makes sense. If, on the other hand, the goal is to provide relevant data to interested parties, this indicates a lack of impartiality that may make the data suspect. There are plenty of people who write about adoption that would ignore this research as pro-adoption rhetoric based on this belief.

Terminology issue - referring to all children with non-traditional parent relationships as "orphans" is a significant problem. I don't know any adoptees who describe themselves using this term, and it has very negative connotations for any members of a first family. In general the term orphan specifically carries the connotation that a child is separated from their biological parents by death. I strongly urge that this term be replaced with something less emotionally charged.

The preamble for "The Parents" again seems unnecessary and potentially inflammatory. It isn't really possible for an infographic to appropriately investigate the reasons people have for wanting to adopt children, just as it cannot thoroughly investigate the reasons parents have in placing children with adoptive families. It may be best to leave these attempts to explain motives out of the infographic.

The breakdown of demographic data for adoptive parents is interesting and very clearly presented. I would, however, be very interested in seeing correlative data. What percentage of parents adopt due to infertility or same sex coupling? How do those demographics relate to choices between domestic and international adoption?

The information and resources at the bottom of the graphic are a nice way to wrap up the ideas presented. They do a good job of presenting the information without hitting emotionally charged trigger words.

Thanks for sending this along to me. I hope the feedback is useful. If there's anything you'd like to follow up on, or that I didn't present clearly, please contact me again. It's important to me that information like this, and communication about it, be as clear and deliberate as possible.

Cheers,

I am

The data presented in that inforgraphic is potentially useful. Unfortunately it is filtered through inflammatory language and ideas about the adoption experience that are simply untrue. Future adoption professionals are being taught that it's okay to call everyone who was ever adopted an orphan. The graphic above was the work of a graduate department. This is coming from people who are a thesis away from entering the field. Bad social workers aren't born; they're taught. In order to change the opinions of adoption workers we must also change their education. For many that means educating them about our experiences. For some that means teaching their educators.

The quality of a person's education can dramatically alter their professional development. A high quality education (in this context, one that humanizes everyone touched by adoption) can also enhance personal development. Conversely a poor education does not degrade personal worth. Low quality education can be mitigated with high quality corrective experiences. It is the experience and education that need correction, not the person.

It is possible to confront an idea without confronting the person espousing it. The idea and the person are separate entities. For example, the infographic above presents ideas that are hurtful and ignorant. The people who put it together didn't intend to hurt anyone. They did a lot of work to pull together information and present it in the most useful way they could. Those efforts deserve affirmation. They also need redirection. A little more reflection on the humans represented in the pie charts may have resulted in something profoundly useful and respectful. It is not a character flaw that caused the students to take a misstep.

Even social workers make mistakes. They aren't bad people. They just need enough quality information to make better choices next time. That information has to come from people like us. If we don't tell them what's wrong, how systems fail us, what needs to change, and why it's important to respect every adoption experience, no one will.

Thursday, November 29, 2012

Saturday, November 17, 2012

God's Plan: Cold Comfort or Greater Purpose?

Growing up I attended quite a few churches. My father being an appointed pastor accounted for three of them. My personal exploration accounted for the next seven. Spending that much time around churches and church people increases the likelihood of certain experiences. Being told that misfortune is "all part of God's plan" is one such experience.

There's another group of people that encounter this phrase more than most: anyone involved in an adoption. Couples struggling with infertility are often "consoled" this way. First families are told this to ease the pain and uncertainty of placing their children with couples they barely know. Adoptees often hear this to help erase the pain of their loss and difference. There is one significant problem with this.

It doesn't work at all. Though the intent is compassion, these words have none. They don't validate the person in pain. They don't even address presence of pain.

Instead these words serve a purpose entirely contrary to their common intent. They separate the supporter from the experience of the wounded. If pain is all "part of God's plan" the listener has no culpability in the situation. There is no risk for the onlooker because success is assured. If pain is part of the plan it takes on a moral quality. The pain becomes good pain. The pain is good because the person experiencing it is participating in "God's plan". The person has become a holy vessel. Holy vessels, uniformly, have been stripped of their humanity.

If this is true, why on Earth does this phrase get so much use? Because it comforts the supporter, not the vulnerable. The person in hardship experiences good pain. If the pain is good, for the individual and the world, there is no need to alleviate it. The person who would normally be called to take action has been let of the hook. Situations that are intolerable to think of, let alone witness, are acceptable if they are calculated sacrifices made by a faultless entity.

What happens to our attitudes if these sacrifices are not calculated losses outweighed by their benefit? Suddenly a person's pain is excruciating instead of purifying. A child placed for adoption is a desperate attempt to salvage some good from a terrible situation. Adoption is no longer a beautiful miracle. Unplanned pregnancies lose the glow of purpose. Suddenly rape is just rape and incest is shown fully as the horror it is

"It's all part of God's plan" isn't comfort to those who need it. It's a "Get Out Of Jail Free" card for those called upon to be the comfort others need.

There's another group of people that encounter this phrase more than most: anyone involved in an adoption. Couples struggling with infertility are often "consoled" this way. First families are told this to ease the pain and uncertainty of placing their children with couples they barely know. Adoptees often hear this to help erase the pain of their loss and difference. There is one significant problem with this.

It doesn't work at all. Though the intent is compassion, these words have none. They don't validate the person in pain. They don't even address presence of pain.

Instead these words serve a purpose entirely contrary to their common intent. They separate the supporter from the experience of the wounded. If pain is all "part of God's plan" the listener has no culpability in the situation. There is no risk for the onlooker because success is assured. If pain is part of the plan it takes on a moral quality. The pain becomes good pain. The pain is good because the person experiencing it is participating in "God's plan". The person has become a holy vessel. Holy vessels, uniformly, have been stripped of their humanity.

If this is true, why on Earth does this phrase get so much use? Because it comforts the supporter, not the vulnerable. The person in hardship experiences good pain. If the pain is good, for the individual and the world, there is no need to alleviate it. The person who would normally be called to take action has been let of the hook. Situations that are intolerable to think of, let alone witness, are acceptable if they are calculated sacrifices made by a faultless entity.

What happens to our attitudes if these sacrifices are not calculated losses outweighed by their benefit? Suddenly a person's pain is excruciating instead of purifying. A child placed for adoption is a desperate attempt to salvage some good from a terrible situation. Adoption is no longer a beautiful miracle. Unplanned pregnancies lose the glow of purpose. Suddenly rape is just rape and incest is shown fully as the horror it is

"It's all part of God's plan" isn't comfort to those who need it. It's a "Get Out Of Jail Free" card for those called upon to be the comfort others need.

Wednesday, November 14, 2012

OAR Interview Project 2012: Meet Jenn

Last year I had the opportunity to work with Mrs R, an adoptive mother who writes at The R House. It was a great chance for both of us to learn about perspectives and experiences wildly different than our own (the interviews can be found here and here). This year Heather has done a great job yet again. I had the pleasure of getting to know Jenn, an adult adoptee. She is candid in her discussion of searching for her origins, making meaning of her experiences, and both the beauty and ugliness of adoption. She is very active in the online community, both on her blog and as a regular contributor to Lost Daughters.

Please introduce yourself to readers who may not be familiar with your blog.

For

starters, my name is Jenn. I’m twenty-five years old, and I was

adopted as an infant. When I was twenty-one, I started seriously

searching for my natural family members. Once I made up my mind to

really search, it took less than twenty-four hours to find my natural

parents thanks to the wonderful Internet. I reached out to my natural

mother and we started emailing back and forth. Just under a year later I

reached out to my natural father and started to get to know him.

I've since met both parents and my two sisters recently found out about

me. I’m currently getting to know the two of them and we’re all

learning how to fit into each other’s lives. I’m also living at home

with my adoptive parents and my adoptive sister, something that adds

other challenges to the mix as well.

What got you started blogging? What keeps you coming back? Is there a disparity there worth exploring?

I started blogging after my reunion experience with my natural mother feel apart. Things with my natural father were going wonderfully, but I was in a rough place because I was trying to balance my fear and excitement. It was a hard time for me and I looked online for support. I’d been following several adoptees on their blogs for a few months and figured that maybe it would help me to write about what I was going through. I was never successful at journaling because there was no accountability. By blogging, I felt as though I owed my readers a blog post every day. I’m an all or nothing sort of girl so I just sort of jumped in. I kept coming back because it helped. I could go back and read what I was thinking and feeling and see the progress. My readers give me valuable feedback and insights. I had the opportunity to meet some of my readers which inspired me to keep going. I think I started it for me, and while I still blog for me, it’s become something more at this point.

You obviously read quite a few adoption blogs. Can you talk about

why you read the blogs you do (individual blogs and/or categories of

blogs)?

The first few blogs that I started reading were

adoptee blogs. They were people who had been through something similar

and I devoured their stories. As much as it stunk that someone else had

gone through something so horrible, there was something comforting in

the fact that I wasn't alone. And I was able to hope when people wrote

about the good things. If they could be happy and functioning humans

after rejection, I could get there too someday. After I started

blogging, I had several natural mothers start commenting on my blog. I

wanted to get to know my readers better so I started reading their

blogs, which opened up a whole new category for me. I started to see

where my natural mother might be coming from. She may not feel the same

way as these women, but I started to see that there were shades of grey

from these amazing women. Last year during this interview project I

was paired up with an adoptive parent. I loved her story and her blog

and loved how she was doing her part to learn about what her daughter

might go through someday. So I now read several adoptive parent blogs,

especially the ones who focus on listening to adult adoptees and

constantly educate themselves on adoption related issues in case their

child ever experiences them.

Has blogging (as a writer or a reader) significantly affected

your thoughts/feelings on adoption in general, or your personal adoption

experience?

My thoughts and feelings have shifted over

time. I’m much more educated now that I used to be. For example, I

never thought about the language that I use to describe adoption before.

I've since read several very well written blog posts about why certain

language is offensive and the history behind it. I've since altered my

language. I used to not see a problem with adoption. I

personally didn't have a problem obtaining a passport. Blogging as

taught me it’s a legitimate concern for other adoptees. I've learned

from them about problems that exist in the system. Before I started

blogging, I couldn't tell you what an original birth certificate was and

I had no idea mine was sealed. This past year I joined a demonstration

in the fight to open records. I've learned and grown as I've been

reading and blogging. My ideas have shifted and I've become more

comfortable with my stance. There will always be grey and I appreciate

it. But I've see firsthand some of the wrongs and I think that we owe

it to ourselves and future adoptees to find ways of fixing the system.

A good start to that would be opening records.

You have described your adoption as being good but difficult. Can you expand on this apparent duality?

I love my adoptive parents and my adoptive family. I had a fairly normal childhood. I got a great education, found some amazing friends, and have experienced some amazing things. I've met the most amazing guy in the world I’m going to marry next year. I love who I am as a person and I know that some of the great qualities I love about myself have come from my adoptive parents since being in reunion. Being adopted has always been a part of who I am and I do believe it’s helped to shape me as a person. Growing up, I was more tolerant of other’s differences because I didn't know what my own background was. I grew up in a wealthy town but the reason I’d been given for my adoption was that my natural mother was young and poor. It was hard for me to judge those will less in my town because I came from a place that had decidedly less. I think that way of growing up had its merits. On the other hand, I wish I hadn't been adopted in an abstract way. I wish I had grown up around people I looked like. I wish I had parents who said “I was just like you at that age!” I wish my personality lined up more with the people who raised me. I would have loved to grow up knowing about my ethnic background and knowing my family history. A family medical history would have drastically altered my childhood. That’s not to say that I wish I’d grown up with my natural parents. Who knows what my life would have been like if I’d been raised by them? It might have been better, it might have been worse. It would have been a different life. I’m sure if I was the girl I would have been if I’d been raised by them, I’d say I couldn't imagine growing up any other way. But I’m not that girl. I’m me, the person raised by my adoptive family and the person who grew up with many missing puzzle pieces. So while my life is actually good, I wish I hadn't had to face so many challenges and go through pain in reunion in order to get to this particular place.

Is there anything you wish you could tell every adoptive parent?

Two

things. First, be honest and upfront from day one. Sometimes the

truth hurts. Sometimes the situation it really unpleasant. And I

understand 100% that you want to protect your children. But when we

don't know the truth, adoptees often fill in the blanks. If you asked

me what I thought of my natural parents when I was ten, I would have

told you they were probably crack heads or something. That's what I

thought because my adoptive parents never sat down and explained my

situation to me. My natural parents are actually upstanding members of

the community. They are both active in their church, raised two amazing

daughters, and are pretty neat people. My parents didn't know

everything, but they did know some things that would have helped. My

natural father was in the army. That single piece of knowledge would

have gone a long way while I was growing up. Second, listen. I didn't

tell my adoptive parents about what I was going through. I wanted to

protect them from my feelings because I didn't think I had a right to

feel the way that I did. Most of the time I was a happy go lucky kid,

but sometimes thoughts about those crack head parents I had invaded my

mind. Kids on the playground can be mean. So when I did actually talk

about things, I needed my adoptive parents to listen. For the most

part, they did, but I think that's something that every adoptive parent

has to work extra hard at. Even know when I'm in reunion, I need my

adoptive parents to listen to me and hear what I'm saying. When I tell

them that it's not about them, it's about me, I need them to hear it.

When I tell them that I need them to just let me vent about the

process, I need them to let me instead of trying to get me to see things

from the other side. So adoptive parents need to be honest with their

children from the beginning and to listen to what their children are

saying, even when they are adults.

Is there anything you wish you could tell every first parent?

At

some point, my natural parents walked away. They may have had

excellent reasons for doing so. And my adoptee brain understands those

reasons. My adoptee brain was able to forgive my natural parents for

walking away a long time ago. I don't agree with all their reasons, but

I understand why they did it. The thing is, my adoptee heart still

feels like they walked away and that hurts. No matter how good the

reasons were, my adoptee heart still hurts from time to time. Sometimes

I get mad about it. Sometimes I need space to get over it. None of

these things have anything to do with the actual reasons themselves. So

when these times roll around (and I think they do for a lot of

adoptees), I know that for me, I just need a little understanding. I

need my natural parents to not get defensive and understand that no

matter what, my adoptee heart is still going to feel that way. In fact,

what I want to hear is that they are sorry for doing that to me and

that they love me. My heart needs to feel like they aren't going to

walk away from me again. And my heart needs to hear it over and over

again. I wish my brain and my heart could get on the same page, but

they can't. And I've heard a lot of adoptees say this same thing. So

understand that sometimes your adopted child may lash out or feel hurt

about things. Its a side affect. He or she probably wishes that they

could control it, but they probably can't. And what they need most is

reassurance, love, and understanding.

Is there anything you wish you could tell every adoptee?

We

all feel differently. And that's OK. One person's feelings or

experiences cannot take away from another. So if someone is happy to be

adopted, then that's fantastic for them. If someone is unhappy to be

adopted, then that's valid too. Just because one person is happy

doesn't make everyone happy, and just because one person is sad doesn't

make everyone sad. I think that we all need that reminder sometimes,

especially when blogging. One adoptees truth is not everyone's truth.

We all are individuals and need to be respected as such.

Are there any specific examples of the support adoptees may need

that differs from others (while growing up or as adults)? Are there any

specific examples of ways in which the support adoptees need is the

same as others (while growing up or as adults)?

Adoptees are people too! We need support just like

everyone else for life's challenges. If I go through a bad breakup, I

need love and support just like my non-adopted friend does. I will

probably process my breakup differently (for myself, it would probably

trigger abandonment issues) but I still need someone there who's willing

to listen and hold my hand. I still need a shoulder to cry on when I

loose someone I love, the same as anyone else. I still want to

celebrate when I get a promotion (for me it might feel extra special

because I've always felt like I have something to prove), and I still

want to go to the bar and have a celebratory drink, the same as any of

my friends. There are small difference in my experience but then

again, my friends all have their own motivations as well. For all I

know, perhaps a friend had a traumatizing experience involving a corpse

when he was a child (it could happen) so death triggers him differently.

Perhaps a friend miscarried a child and thus her breakup with the

father is a lot harder to process. We all have various things that

separate us as adults (and children too) but we somehow manage to get

along. I think that listening is key, being supportive, and learning

that while we can't fully understand, we can still be there for each

other.

In many adoptee blogs and forums, a common theme encountered is

"difference". It is often describing how the adoptee experience is

"different" and how "no one can understand" the experience who is not an

adoptee. As someone who is not an adoptee, this theme appears to

strengthen alienation by association. Can you talk a little about your

experience with alienation, difference, and community?

I think part of this problem (and yes, it's a problem) is that there really is a difference there. I was cut off from my family completely and totally. The closed adoption system made sure I had no contact with anyone I was genetically related to growing up. I never heard "You look just like Aunt Suzie at that age!", "You've got Uncle Fred's eyes", or "I was just like you when I was young! I guess this is payback..." My relatives still said things like that, just about other people. I always felt like I was on the outside looking in with my face pressed up against the glass. I got strange looks in public. People commented from time to time. And people always looked for similarities that weren't there when they were introduced to my sister and me. I learned that those things were important with how hard people would try to find similar. Apparently we have the same facial structure (we don't really). I've heard that at least ten times. The thing is, we saw other people who weren't adopted. I could see that my best friend looked a lot like her mom and her brother. I saw that my cousins all laughed the same way as my mom. And I grew up feeling different. So that difference is there, and it's something that a lot of us have been aware of since we were small children (noting here that not everyone has this experience and some children were matched with families they would probably grow to look like). I've seen instances online where some people (a small number) have tried to tell adoptees that we aren't really different. I've seen people try to minimize that difference and act like it doesn't matter. Only it does. And that's when I've noticed adoptees getting defensive. It's also hard to understand something that you haven't been through. It's not individual to our community by any means. I identify as a white straight female. I will never understand what it's like to be a Native American lesbian. I can listen to her story. I can sympathize, but not empathize. I think it's a glaring problem with our community because adoptees aren't supposed to be different (at least when I was born) and being adopted wasn't supposed to be different from being raised in the family you were born too. So people don't understand this difference and try to explain it in other ways instead of accepting that we can't fully know the other's experiences from their point of view and work on the sympathy side of things. Instead of finger pointing or having an "us vs them" attitude, I think as a community we need to embrace the differences and move forward together. Then again what do I know?

Can you talk about the commonalities and differences of

experience between adoptees and non-adoptees entering adulthood and

struggling to establish a sense of "self"?

Well,

I was adopted as an infant, so I don't really have a point of reference

for the non-adopted. I do know lots of non-adopted people so I guess I

could take a stab at it. I think that in general, our sense of self

comes from our history, and our experiences I'm a firm believer that

you have to know the past going into the future. History has a tendency

to repeat itself, and I think that we can learn a lot from mistakes and

successes in the past. For adoptees (closed adoptions), we don't

usually know our past. It's hard to move forward when you don't know

where you come from. History is important. At the same time, I know

that I grew into my sense of self based on a number of experiences I

had. Being adopted had nothing to do with my love for dance and the

experiences and lessons I learned from that. I have friends who

identified as dancers as well, and most were not adopted. So in that

sense, there are commonalities. On the other hand, I have friends who

used to brag about having ancestors who came over on the Mayflower.

That was a huge part of their "self" and that piece of history was

important to them. It was a part of their truth and personal identity.

I didn't have that. I had to fill in the blanks or take guesses, but

there were a lot of question marks for me. So in that sense, we're

different. As I learn my history, I can feel my view of myself change

slowly as it becomes more complete with less missing pieces. It's an

odd thing to happen as an adult, but now I know that I had ancestors in

the US before the Revolutionary War too. I have my family tree traced

back to the 1400's on one branch. So I guess now I'm trying to find a

way to catch up with everyone else!

Thank you again to Jenn for your honesty and patience, to Heather for all your hard work, and to all the Interview Project participants for your courage. Jen's interview with me is here. Be sure to check out the Open Adoption Bloggers page for more exciting projects in the future as well as the exhaustive blog roll for more perspectives to read.

Thank you again to Jenn for your honesty and patience, to Heather for all your hard work, and to all the Interview Project participants for your courage. Jen's interview with me is here. Be sure to check out the Open Adoption Bloggers page for more exciting projects in the future as well as the exhaustive blog roll for more perspectives to read.

Thursday, November 8, 2012

Are You F___ing Serious?!

There are several things in the works at the moment that I'm looking forward to posting. Unfortunately, all of those require more polish and editing before they're fit for public consumption. Despite this, I feel the need to share something.

While poking around online, Google Adsense has shown that it's finally started tracking my online behavior. So now I'm seeing ads for adoption agencies. This is an indication that I need to review my privacy controls and settings. But more importantly, I saw an advertisement today that I find profoundly disturbing.

The phrase highlighted was "you don't have to be perfect to be a perfect parent". For the moment I'm going to ignore the issues I might take with this catch phrase and how poorly it conveys its intended message. What is important, however, was the associated image. It was a screen capture from The Odd Life of Timothy Green.The website, AdoptUSKids.org is using pop culture references in an attempt to make adoption more accessible. That makes sense and has been put to good use in many efforts to normalize ideas mass media isn't ready to embrace. It still sickens me a bit, but at least I understand it. The problem I have with this is the pop culture material being referenced.

If adoption professionals are going to use pop culture to approach people online about accepting adoption, maybe they should consider using material that accepts adoption. I'm not going to rehash the review of the film I did in August. It's not worth your time and it certainly doesn't deserve that much space in anyone's brain. But I can't help but wonder what the hell these people are thinking emblazoning on their advertisements images from a film that encourages emotionally damaging ideas about adoption. The only conclusion I can come up with is the person who thought up this ad campaign either never saw the movie, shouldn't be working in the adoption industry, or has firmly lodged their cranium into one of their own orifices.

Thank you for putting up with this rant. I hope you have a pleasant day.

While poking around online, Google Adsense has shown that it's finally started tracking my online behavior. So now I'm seeing ads for adoption agencies. This is an indication that I need to review my privacy controls and settings. But more importantly, I saw an advertisement today that I find profoundly disturbing.

The phrase highlighted was "you don't have to be perfect to be a perfect parent". For the moment I'm going to ignore the issues I might take with this catch phrase and how poorly it conveys its intended message. What is important, however, was the associated image. It was a screen capture from The Odd Life of Timothy Green.The website, AdoptUSKids.org is using pop culture references in an attempt to make adoption more accessible. That makes sense and has been put to good use in many efforts to normalize ideas mass media isn't ready to embrace. It still sickens me a bit, but at least I understand it. The problem I have with this is the pop culture material being referenced.

If adoption professionals are going to use pop culture to approach people online about accepting adoption, maybe they should consider using material that accepts adoption. I'm not going to rehash the review of the film I did in August. It's not worth your time and it certainly doesn't deserve that much space in anyone's brain. But I can't help but wonder what the hell these people are thinking emblazoning on their advertisements images from a film that encourages emotionally damaging ideas about adoption. The only conclusion I can come up with is the person who thought up this ad campaign either never saw the movie, shouldn't be working in the adoption industry, or has firmly lodged their cranium into one of their own orifices.

Thank you for putting up with this rant. I hope you have a pleasant day.

Friday, October 5, 2012

Hard as Hell: The New Normal

I've been tight lipped about a lot of changes that have been going on in my life of late. One reason is that I needed the chance to tell all the people in my life about what is going on in person. It's rather rude for family members to learn about momentous changes in one's life through a blog entry. The second reason is that it is more comfortable to talk about abstract concepts than the difficult, sometimes brutal, circumstances faced in daily life. Finally, I really hate complaining about my life. I feel it makes me sound whiny and potentially self centered. After all, how bad do I really have it? I have food to eat. That counts as victory.

The truth of the matter is my life has been quite stressful lately and there's a reason I don't like talking about it here. I've fallen prey to self censorship. I don't want to talk about my life stress. It is uncomfortable to face and to admit to others. The real bear of it is the sense I must represent all birthfathers. I must be successful to prove that birthfathers can be successful. I should be emotionally/relationally well balanced to show that birthfathers can be so.

Related to those misplaced feelings of responsibility is my embarrassment. You see, Prof Plum and Ms Scarlet poke through the blog from time to time. I've been doing my best to put on the brave face around them. I really don't want them to think I'm some sort of unstable screw up. Their opinions matter to me, and our relationship is important to me. I have been keeping things under wraps with the classic "things are a little tough but we're okay" explanations. We will be okay, but that isn't why I'm brushing aside others' concern for Athena and me. I don't want to need others' support, and I particularly don't want to lean on Ms Scarlet and Prof Plum for support. I wish I could tell you why. I honestly don't know. Though I do have a couple theories.

I've encountered people who have felt the birth family of their child took advantage of the open adoption relationship. In a very concrete and obvious manner most adoptive families have more resources available than first families do. That holds true in our situation as well. I don't want there to be any question in anyone's mind about our relationship being built on respect. I loath the idea of that respect being tarnished by a one sided need for support. Said out loud this idea sounds a little ridiculous. After all a relationship based on respect doesn't require that everyone be an island with no needs nor expectations. But that doesn't change the traction this idea has in my head.

There's a lot of pressure as an involved birth parent to live a spotless life after the placement of your child. A desire to prove worthy of a relationship with your kid takes hold and is very difficult to shake. It's as though I must prove that I would be a fit parent to my son and be able to provide the stable and respectable life that would make an adoption entirely unnecessary. This pressure is mostly self imposed, but there are some practical realities that reinforce the message.

Since open adoption agreements aren't legally enforceable (anywhere, to the best of my knowledge) the first family has to be sound enough to ensure further contact with the adoptive family. In short, if I'm too needy, my life too unstable, or my presence vicariously too stressful, the relationship can end with no notice. If the difficulties of my daily life are too unpleasant to think about, I may never see my son again. Again this sounds ridiculous when said aloud, especially in the context of my relationship with Festus' parents. But I can't shake the idea, in part because I know it has happened. I've had contact with several first parents who have been denied relationships with their children. The apparent cause was the convenience of the adoptive family. I wasn't there personally. I don't know the totality of those experience and relationships. But in the murky world of private adoption I would be surprised if birth parents weren't pushed aside because their lives made the adoptive family uncomfortable.

It is with all this weighing on my mind that I tell people "I'll be okay". But I am not okay right now. I quit my job at the university because I could no longer keep up physically, and I was tired of my boss throwing me under the bus every chance he got. Bald faced lies at my last performance review were the writing on the wall for me. I don't like day dreaming about meeting people in parking lots with framing hammers, and that's exactly what that job did to me. My "rocky-but-sustainable" transition from that job to freelance work and diversified income has been a rude awakening. With a gross income for the month of September of $0, I must also leave my apartment. Athena and I will not be able to live together for a while. I feel as though I've been free falling for a few months. Watching my savings disappear, closing bank accounts, I've tried selling some possessions to buy groceries. I'll be moving into my parent's home, but I don't know if I can afford the rent they will charge me either. Any rent is steep without a job. But I keep telling people I'll be okay. If I say it enough maybe I will be. It's more a prayer than something I believe.

So there you have it. Prof Plum, Ms Scarlet, I'm sorry I haven't been more honest with you. It's just been a tough couple of months.

The truth of the matter is my life has been quite stressful lately and there's a reason I don't like talking about it here. I've fallen prey to self censorship. I don't want to talk about my life stress. It is uncomfortable to face and to admit to others. The real bear of it is the sense I must represent all birthfathers. I must be successful to prove that birthfathers can be successful. I should be emotionally/relationally well balanced to show that birthfathers can be so.

Related to those misplaced feelings of responsibility is my embarrassment. You see, Prof Plum and Ms Scarlet poke through the blog from time to time. I've been doing my best to put on the brave face around them. I really don't want them to think I'm some sort of unstable screw up. Their opinions matter to me, and our relationship is important to me. I have been keeping things under wraps with the classic "things are a little tough but we're okay" explanations. We will be okay, but that isn't why I'm brushing aside others' concern for Athena and me. I don't want to need others' support, and I particularly don't want to lean on Ms Scarlet and Prof Plum for support. I wish I could tell you why. I honestly don't know. Though I do have a couple theories.

I've encountered people who have felt the birth family of their child took advantage of the open adoption relationship. In a very concrete and obvious manner most adoptive families have more resources available than first families do. That holds true in our situation as well. I don't want there to be any question in anyone's mind about our relationship being built on respect. I loath the idea of that respect being tarnished by a one sided need for support. Said out loud this idea sounds a little ridiculous. After all a relationship based on respect doesn't require that everyone be an island with no needs nor expectations. But that doesn't change the traction this idea has in my head.

There's a lot of pressure as an involved birth parent to live a spotless life after the placement of your child. A desire to prove worthy of a relationship with your kid takes hold and is very difficult to shake. It's as though I must prove that I would be a fit parent to my son and be able to provide the stable and respectable life that would make an adoption entirely unnecessary. This pressure is mostly self imposed, but there are some practical realities that reinforce the message.

Since open adoption agreements aren't legally enforceable (anywhere, to the best of my knowledge) the first family has to be sound enough to ensure further contact with the adoptive family. In short, if I'm too needy, my life too unstable, or my presence vicariously too stressful, the relationship can end with no notice. If the difficulties of my daily life are too unpleasant to think about, I may never see my son again. Again this sounds ridiculous when said aloud, especially in the context of my relationship with Festus' parents. But I can't shake the idea, in part because I know it has happened. I've had contact with several first parents who have been denied relationships with their children. The apparent cause was the convenience of the adoptive family. I wasn't there personally. I don't know the totality of those experience and relationships. But in the murky world of private adoption I would be surprised if birth parents weren't pushed aside because their lives made the adoptive family uncomfortable.

It is with all this weighing on my mind that I tell people "I'll be okay". But I am not okay right now. I quit my job at the university because I could no longer keep up physically, and I was tired of my boss throwing me under the bus every chance he got. Bald faced lies at my last performance review were the writing on the wall for me. I don't like day dreaming about meeting people in parking lots with framing hammers, and that's exactly what that job did to me. My "rocky-but-sustainable" transition from that job to freelance work and diversified income has been a rude awakening. With a gross income for the month of September of $0, I must also leave my apartment. Athena and I will not be able to live together for a while. I feel as though I've been free falling for a few months. Watching my savings disappear, closing bank accounts, I've tried selling some possessions to buy groceries. I'll be moving into my parent's home, but I don't know if I can afford the rent they will charge me either. Any rent is steep without a job. But I keep telling people I'll be okay. If I say it enough maybe I will be. It's more a prayer than something I believe.

So there you have it. Prof Plum, Ms Scarlet, I'm sorry I haven't been more honest with you. It's just been a tough couple of months.

Wednesday, September 26, 2012

The Odd Life Of Timothy Green - A Film Review

Typically a character named in the title of a movie is the main point of interest. Sometimes the character is talked about more than they are seen (as in Saving Private Ryan). But most of the time a film named for a character will be about that character (such as Forest Gump or The Talented Mr. Ripley). This is not the case in The Odd Life Of Timothy Green.

A more honest title may have been "The Odd Life Of Timothy MacGuffin". Timothy is not the main character of the film, and in truth is barely addressed as being a person. When the character shows up he is fully self actualized. Timothy has no needs at all. As a result Timothy, as a character, is utterly static. He displays no growth, nor even hardship, throughout the film. This means his parents are never called on to support him in any way. Instead, Timothy supports his parents as they grapple with changes in their lives brought on by Timothy's presence. In a disturbing turn, one of the hardest adaptations his parents make is living with a shred of integrity. Every scene throughout the film in which his parents appear to provide emotional support for Timothy, the motivation appears to be embarrassment rather than concern for his emotional well being.

Rather than discussing the experience a family goes through in developing bonds or experiencing estrangement as a result of adoption, TOLOTG (The Odd Life of Timothy Green) is the navel gazing adventure of hopeful parents obsessed with familial obligation. More screen time is given to Jim and Cindy Green interacting with their biological family members than with their son. The implication is, the way Timothy affects his parents existing relationships, is more important than his relationship with them. In effect, the story is about how neat it would be to become a parent, not about parenting. In fact the parents never really discussed why they want to be parents in the first place. The film assumes everyone knows why it is important to have children. For some people it may be troubling to think this idea needs defense. But the truth is the miraculously convenient events of this story do demand more justification than "it's the next thing to do" or "everyone wants kids". One evening Jim and Cindy Green are trying to mourn their chance to have a child biologically, and the next they are acclimating to having their own child (SPOILER) in the middle of a family reunion (CLOSE SPOILER). The transition from one experience to the other involves bewilderment, then total acceptance. There are no tears or frustration. They don't skip a beat. Frankly there is no emotional honesty at all.

That's the real achilles heal to the story of TOLOTG. There is no emotional honesty or depth at any point. The closest it gets is when we see Timothy's friend cry in the last quarter of the film. The children are the only people who show any honesty throughout this movie, only with one another, and it only happens a handful of times. Jim and Cindy Green weren't represented even vaguely accurately as humans. Their decisions and mistakes never had any significant impact on their lives. (SPOILER) At one point Cindy loses her job, because Timothy inspired her to actually be honest. This affects one line of the script. Jim responds saying "thing's will be tight but we'll be alright". It's never mentioned again. Shortly thereafter Jim is given responsibility for laying off several of his coworkers. This puts him in a bad mood for exactly six seconds of screen time (CLOSE SPOILER). So Jim's in a terrible mood, but it's fixed when Cindy and Timothy decide to follow Jim into the living room with dinner. They have a candle-lit picnic dinner inside, which everyone loves.

Throughout the course of the picnic dinner, Timothy does little else than stare adoringly at his parents. The exception to this is when he, yet again, solves his parents' problems for them. That highlights the second fatal flaw of this movie; all the children represented have reversed relationships with their parents. Each child with a significant role (both of them) are self actualized, confident, unflappable individuals. The parents spend their time bouncing off these monolithic children until they learn the lesson in that scene. Then everyone moves on to the next scene and the next lesson. Throughout this process none of the children show any growth or development. In fact I'd go so far as to say they show no memory either. This isn't just poor writing, this is dangerous.

Showcasing children without needs, with mountain-like emotional stability, and total self knowledge in a theoretically child centered movie is damaging. It shames the children in the audience for having needs. The children on the screen are perfect, so the children in the audience are pressured to be the same. The children on the screen make no mistakes, and therefore the viewer is called to the same standard. It's important to remember that the genre of "Family Films" functions to instruct us what the modern family is supposed to be like. These are didactic movies. As such I feel it is damaging, even damning, to expect children to identify with the most alien of experiences presented to them; perfection and isolation.

Timothy doesn't appear to be isolated, but he is. He has one friend who is emotionally affected by him. In his parents lives he is a lifestyle prop. Timothy is the means to the end. (SPOILER) This is rather openly displayed when Timothy disappears, yet the viewer never sees his parents mourn. Instead we get to see how happy his parents are when his replacement is delivered. The little girl of Asian descent, who also speaks perfect English, is delivered to their front door literally without any baggage (CLOSE SPOILER). The child has no roots, no baggage, and no past. There are no ethical quandaries about adoption because the children have no origin. The children literally come from no where and are delivered like a pizza.

There are a lot of things that could have been incorporated into this story to spur honest conversation about adoption. Imagine if Timothy had a learning disability, or heaven forbid a physical abnormality that actually affected how he functioned. He would have had unavoidable needs that could only be attended to properly by his caregivers. Things get even more interesting if Timothy were raised in a poor neighborhood in a city. But I think the real elephant in the room is this; what if Timothy were ethnically or culturally different than his parents? The truth is a Disney film couldn't survive the possibility of Timothy being black, let alone admitting to the serious problems of fraud, theft, and human trafficking in international adoptions. But worst of all, the idea of adopting a healthy child from people in the same town can't even be considered. Domestic adoption is hinted at by the clear English spoken by the little girl at the end of the film, yet the combination of her name and the casting choice is clearly intended to bring international adoption to mind. I think the real purpose for the girl speaking English without difficulty is to underline the idea that this adoption incurs no difficulties at all.

Much like Juno, The Odd Life Of Timothy Green is a film about people who aren't affected by anything that happens around, or even directly to, them. The overall message is like cotton balls soaked in anti-freeze; it is light, fluffy, sickly sweet, and toxic. The dad only has dad quality problems (mad at his dad, trouble at work), the mom has mom quality problems (pressure of familial obligation, over identification with child's embarrassment, can't "love" boss at work) and the children have no problems of any consequence (the deep dark secret of the friend is, SPOILER, a birthmark CLOSE SPOILER). I expected to be violently angry after watching this film. Instead I felt scummy and mildly nauseous.

But this begs the question - why did I even see this movie if I expected to hate it so much? I readily admit that I'm giving this movie more publicity by discussing it at all, and I'd much rather see it disappear entirely. My concern is with the number of positive reviews I've seen for the movie by writers who care about adoption. In the effort to attain public acceptance, I'm afraid some people are ready to latch on to any kind of acceptance. The Odd Life Of Timothy Green claimed to be a movie about adoption. But the kind of adoption it avoids talking about, for one hour and forty five minutes, is a terrible one. It's the kind of adoption that ruins lives and keeps children from their past. It ignores the experiences of both adoptees and first parents. Instead of representing the experience of prospective adoptive parents, the focus is solely Jim and Cindy's comfort. As it relates to adoption this movie is horrible and somewhat insidious. If we try to relate it to foster care, this movie is fucking evil.

A more honest title may have been "The Odd Life Of Timothy MacGuffin". Timothy is not the main character of the film, and in truth is barely addressed as being a person. When the character shows up he is fully self actualized. Timothy has no needs at all. As a result Timothy, as a character, is utterly static. He displays no growth, nor even hardship, throughout the film. This means his parents are never called on to support him in any way. Instead, Timothy supports his parents as they grapple with changes in their lives brought on by Timothy's presence. In a disturbing turn, one of the hardest adaptations his parents make is living with a shred of integrity. Every scene throughout the film in which his parents appear to provide emotional support for Timothy, the motivation appears to be embarrassment rather than concern for his emotional well being.

Rather than discussing the experience a family goes through in developing bonds or experiencing estrangement as a result of adoption, TOLOTG (The Odd Life of Timothy Green) is the navel gazing adventure of hopeful parents obsessed with familial obligation. More screen time is given to Jim and Cindy Green interacting with their biological family members than with their son. The implication is, the way Timothy affects his parents existing relationships, is more important than his relationship with them. In effect, the story is about how neat it would be to become a parent, not about parenting. In fact the parents never really discussed why they want to be parents in the first place. The film assumes everyone knows why it is important to have children. For some people it may be troubling to think this idea needs defense. But the truth is the miraculously convenient events of this story do demand more justification than "it's the next thing to do" or "everyone wants kids". One evening Jim and Cindy Green are trying to mourn their chance to have a child biologically, and the next they are acclimating to having their own child (SPOILER) in the middle of a family reunion (CLOSE SPOILER). The transition from one experience to the other involves bewilderment, then total acceptance. There are no tears or frustration. They don't skip a beat. Frankly there is no emotional honesty at all.

That's the real achilles heal to the story of TOLOTG. There is no emotional honesty or depth at any point. The closest it gets is when we see Timothy's friend cry in the last quarter of the film. The children are the only people who show any honesty throughout this movie, only with one another, and it only happens a handful of times. Jim and Cindy Green weren't represented even vaguely accurately as humans. Their decisions and mistakes never had any significant impact on their lives. (SPOILER) At one point Cindy loses her job, because Timothy inspired her to actually be honest. This affects one line of the script. Jim responds saying "thing's will be tight but we'll be alright". It's never mentioned again. Shortly thereafter Jim is given responsibility for laying off several of his coworkers. This puts him in a bad mood for exactly six seconds of screen time (CLOSE SPOILER). So Jim's in a terrible mood, but it's fixed when Cindy and Timothy decide to follow Jim into the living room with dinner. They have a candle-lit picnic dinner inside, which everyone loves.

Throughout the course of the picnic dinner, Timothy does little else than stare adoringly at his parents. The exception to this is when he, yet again, solves his parents' problems for them. That highlights the second fatal flaw of this movie; all the children represented have reversed relationships with their parents. Each child with a significant role (both of them) are self actualized, confident, unflappable individuals. The parents spend their time bouncing off these monolithic children until they learn the lesson in that scene. Then everyone moves on to the next scene and the next lesson. Throughout this process none of the children show any growth or development. In fact I'd go so far as to say they show no memory either. This isn't just poor writing, this is dangerous.

Showcasing children without needs, with mountain-like emotional stability, and total self knowledge in a theoretically child centered movie is damaging. It shames the children in the audience for having needs. The children on the screen are perfect, so the children in the audience are pressured to be the same. The children on the screen make no mistakes, and therefore the viewer is called to the same standard. It's important to remember that the genre of "Family Films" functions to instruct us what the modern family is supposed to be like. These are didactic movies. As such I feel it is damaging, even damning, to expect children to identify with the most alien of experiences presented to them; perfection and isolation.

Timothy doesn't appear to be isolated, but he is. He has one friend who is emotionally affected by him. In his parents lives he is a lifestyle prop. Timothy is the means to the end. (SPOILER) This is rather openly displayed when Timothy disappears, yet the viewer never sees his parents mourn. Instead we get to see how happy his parents are when his replacement is delivered. The little girl of Asian descent, who also speaks perfect English, is delivered to their front door literally without any baggage (CLOSE SPOILER). The child has no roots, no baggage, and no past. There are no ethical quandaries about adoption because the children have no origin. The children literally come from no where and are delivered like a pizza.

There are a lot of things that could have been incorporated into this story to spur honest conversation about adoption. Imagine if Timothy had a learning disability, or heaven forbid a physical abnormality that actually affected how he functioned. He would have had unavoidable needs that could only be attended to properly by his caregivers. Things get even more interesting if Timothy were raised in a poor neighborhood in a city. But I think the real elephant in the room is this; what if Timothy were ethnically or culturally different than his parents? The truth is a Disney film couldn't survive the possibility of Timothy being black, let alone admitting to the serious problems of fraud, theft, and human trafficking in international adoptions. But worst of all, the idea of adopting a healthy child from people in the same town can't even be considered. Domestic adoption is hinted at by the clear English spoken by the little girl at the end of the film, yet the combination of her name and the casting choice is clearly intended to bring international adoption to mind. I think the real purpose for the girl speaking English without difficulty is to underline the idea that this adoption incurs no difficulties at all.

Much like Juno, The Odd Life Of Timothy Green is a film about people who aren't affected by anything that happens around, or even directly to, them. The overall message is like cotton balls soaked in anti-freeze; it is light, fluffy, sickly sweet, and toxic. The dad only has dad quality problems (mad at his dad, trouble at work), the mom has mom quality problems (pressure of familial obligation, over identification with child's embarrassment, can't "love" boss at work) and the children have no problems of any consequence (the deep dark secret of the friend is, SPOILER, a birthmark CLOSE SPOILER). I expected to be violently angry after watching this film. Instead I felt scummy and mildly nauseous.

But this begs the question - why did I even see this movie if I expected to hate it so much? I readily admit that I'm giving this movie more publicity by discussing it at all, and I'd much rather see it disappear entirely. My concern is with the number of positive reviews I've seen for the movie by writers who care about adoption. In the effort to attain public acceptance, I'm afraid some people are ready to latch on to any kind of acceptance. The Odd Life Of Timothy Green claimed to be a movie about adoption. But the kind of adoption it avoids talking about, for one hour and forty five minutes, is a terrible one. It's the kind of adoption that ruins lives and keeps children from their past. It ignores the experiences of both adoptees and first parents. Instead of representing the experience of prospective adoptive parents, the focus is solely Jim and Cindy's comfort. As it relates to adoption this movie is horrible and somewhat insidious. If we try to relate it to foster care, this movie is fucking evil.

Saturday, September 1, 2012

Trying to be Human 101: Passivity in Sacrifice

Trying to be Human 101 digs into human experience and how it effects adoption. Previously I discussed the nature of dignity and provided an excerpt from Jim Gritter's Life Givers. This is the second of several posts within the Trying to be Human 101 series discussing sacrifice.

Sacrifice is a transaction. Typically there is social contract that accompanies sacrifices. When one makes a sacrifice, the belief is the loss will allow that need to be addressed appropriately. An example of this might be a person who takes an additional shift at work, sacrificing time with loved ones, to make more money for living expenses. Because choice is involved the sacrificer can bring their personal power to bear in the situation, thus giving them a sense of control. The weight of the sacrifice can be compared to the need calling for it. Judgement can be made including rational and emotional experiences and a choice is made. But what happens when the tables turn? What if the choice to make a sacrifice is illusory? All too often a sacrifice is made but the perceived contract is not fulfilled. Instead the sacrificer, upon losing their prized subject (be it a relationship, item, situation, or idea), feels powerless and no closer to fulfilling the need that drove the sacrifice in the first place. This experience is all too common in adoption.

I believe this sudden shift of experience is symptomatic of a disturbing reality; birthparents are sacrificed in adoption. This is not always true, but it happens with troubling frequency. The relationship between sacrificer and sacrificed can be subtle and murky, especially when the sacrifices are relationships. Other times it is blatant, as with most international adoptions. The birthparent, rather than making a sacrifice on behalf of their child, is sacrificed. The reason for the sacrifice varies. Sometimes the parent is sacrificed in order to fulfill the adoptive families need for a child to parent. Often the birthfamily is sacrificed in far subtler ways.

A birthparent is most often sacrificed on the alter of social expectation. The birthparent becomes the sacrifice necessary to blot out the apparent sin of conceiving a child in less than ideal circumstances. This ties in directly with the Splendid Doormat. In order to attain social acceptability the first family must sacrifice all claim, personal rights, worth, and dignity in order to achieve a semi-saint status. Once sainted the first family can then, and only then, be considered redeemed from the disgrace of adoption.

This may seem a little far fetched or that I'm dramatizing the point. In reality I'm soft-pedaling this one. A bit of study in art history and especially in film history shows how prevalent these themes are. The hoops for redemption must be jumped through and none of them can be skipped or exchanged. Breaking social mores requires drastic action for redemption, if one can be redeemed at all.

In the case of adoption the process of sacrifice can be either; humbling but important, or destructive and horrible. The way we describe the key difference in English is with voice. In active voice, "I sacrifice", I am making choices and am directly involved in the path of that sacrifice. Though I make a sacrifice I still have some degree of control. In passive voice, "I am sacrificed", I have no say. I have lost the ability to apply my will to the process. Instead I become an element of sacrifice, not an active participant. In adoptions it is extremely dangerous to alloy anyone to sacrifice anyone else. To do so is to strip a person of their humanity. To be sacrificed is to be told one has no say in their future, no right to express personal needs, and no expectation these experiences will change. This might sound familiar.

Even in adoptions where all the adults respect one another and behave with emotional/relational integrity, the adoptee may still feel they have been sacrificed. Obviously no one wants this to be the case. An overwhelming majority of parents want their children to feel loved. This means sacrifices are made on their behalf, but they are not sacrificed themselves. Unfortunately, in adoption, no one can predict how the adoptee will feel about his/her circumstances.

I believe, despite the best of intentions, if an adoptee feels s/he has been sacrificed in their adoption, they have. No one has the right to say otherwise. Parents, where ever they fall on the biology/care continuum, may feel they have done everything right and have nothing to apologize for. But the best intentions cannot countermand the emotional reality of a child. If the adoptee feels s/he was sacrificed it's true. The only thing for a parent to do is face that reality head on and try to pick up the pieces.

When all goes well no one is sacrificed. Instead everyone in the adoption will make sacrifices to support one another. With this mutual support everyone's needs and experiences are respected.

I wish everyone in adoption had this experience. But when it does go wrong, as it can so quickly, telling a person her/his emotional experience is "wrong" only deepens the depersonalization. It is not possible to undo mistakes, but some can be avoided through careful attention. In adoption applying our integrity and compassion to our decisions will help avoid most of these problems. With that in mind it's possible to make an adoption something that really is beautiful. That happens when the sacrifices made are respected and celebrated for being exactly what they are.

Sacrifice is a transaction. Typically there is social contract that accompanies sacrifices. When one makes a sacrifice, the belief is the loss will allow that need to be addressed appropriately. An example of this might be a person who takes an additional shift at work, sacrificing time with loved ones, to make more money for living expenses. Because choice is involved the sacrificer can bring their personal power to bear in the situation, thus giving them a sense of control. The weight of the sacrifice can be compared to the need calling for it. Judgement can be made including rational and emotional experiences and a choice is made. But what happens when the tables turn? What if the choice to make a sacrifice is illusory? All too often a sacrifice is made but the perceived contract is not fulfilled. Instead the sacrificer, upon losing their prized subject (be it a relationship, item, situation, or idea), feels powerless and no closer to fulfilling the need that drove the sacrifice in the first place. This experience is all too common in adoption.

I believe this sudden shift of experience is symptomatic of a disturbing reality; birthparents are sacrificed in adoption. This is not always true, but it happens with troubling frequency. The relationship between sacrificer and sacrificed can be subtle and murky, especially when the sacrifices are relationships. Other times it is blatant, as with most international adoptions. The birthparent, rather than making a sacrifice on behalf of their child, is sacrificed. The reason for the sacrifice varies. Sometimes the parent is sacrificed in order to fulfill the adoptive families need for a child to parent. Often the birthfamily is sacrificed in far subtler ways.

A birthparent is most often sacrificed on the alter of social expectation. The birthparent becomes the sacrifice necessary to blot out the apparent sin of conceiving a child in less than ideal circumstances. This ties in directly with the Splendid Doormat. In order to attain social acceptability the first family must sacrifice all claim, personal rights, worth, and dignity in order to achieve a semi-saint status. Once sainted the first family can then, and only then, be considered redeemed from the disgrace of adoption.

This may seem a little far fetched or that I'm dramatizing the point. In reality I'm soft-pedaling this one. A bit of study in art history and especially in film history shows how prevalent these themes are. The hoops for redemption must be jumped through and none of them can be skipped or exchanged. Breaking social mores requires drastic action for redemption, if one can be redeemed at all.

In the case of adoption the process of sacrifice can be either; humbling but important, or destructive and horrible. The way we describe the key difference in English is with voice. In active voice, "I sacrifice", I am making choices and am directly involved in the path of that sacrifice. Though I make a sacrifice I still have some degree of control. In passive voice, "I am sacrificed", I have no say. I have lost the ability to apply my will to the process. Instead I become an element of sacrifice, not an active participant. In adoptions it is extremely dangerous to alloy anyone to sacrifice anyone else. To do so is to strip a person of their humanity. To be sacrificed is to be told one has no say in their future, no right to express personal needs, and no expectation these experiences will change. This might sound familiar.

Even in adoptions where all the adults respect one another and behave with emotional/relational integrity, the adoptee may still feel they have been sacrificed. Obviously no one wants this to be the case. An overwhelming majority of parents want their children to feel loved. This means sacrifices are made on their behalf, but they are not sacrificed themselves. Unfortunately, in adoption, no one can predict how the adoptee will feel about his/her circumstances.

I believe, despite the best of intentions, if an adoptee feels s/he has been sacrificed in their adoption, they have. No one has the right to say otherwise. Parents, where ever they fall on the biology/care continuum, may feel they have done everything right and have nothing to apologize for. But the best intentions cannot countermand the emotional reality of a child. If the adoptee feels s/he was sacrificed it's true. The only thing for a parent to do is face that reality head on and try to pick up the pieces.

When all goes well no one is sacrificed. Instead everyone in the adoption will make sacrifices to support one another. With this mutual support everyone's needs and experiences are respected.

I wish everyone in adoption had this experience. But when it does go wrong, as it can so quickly, telling a person her/his emotional experience is "wrong" only deepens the depersonalization. It is not possible to undo mistakes, but some can be avoided through careful attention. In adoption applying our integrity and compassion to our decisions will help avoid most of these problems. With that in mind it's possible to make an adoption something that really is beautiful. That happens when the sacrifices made are respected and celebrated for being exactly what they are.

Sunday, July 15, 2012

Trying to be Human 101: The Nature of Sacrifice

Trying to be Human 101 digs into human experience and how it effects adoption. Previously I discussed the nature of dignity and provided an excerpt from Jim Gritter's Life Givers. This is the first of several posts within the Trying to be Human 101 series.

Sacrifice is a strange concept. It is comforting to know that sacrifices are made but we don't want to get very near it. Comfort increases with distance from the individuals making sacrifices. When discussing adoption it is common to acknowledge that first families are making sacrifices. The impact those sacrifices have on adoptees is sometimes respected, but often ignored. The nature of sacrifice is left largely unexplored. If it is thought of frequently, or with depth, it is conjured into existence. Personally confronting sacrifice is an overwhelming experience. We often seek refuge by distancing ourselves from those making the sacrifices that frighten us.

It's important to understand why sacrifice is so uncomfortable. Discussing sacrifice highlights our position relative to the person making the sacrifice. There are a few different roads this can take, but most of them lead to a disconcerting feeling of selfishness or powerlessness. When discussing sacrifices made by others we often feel selfish. Mother Teresa is a good example of this experience. Compared to her work most people feel rather sheepish about their own charitable work or giving. Despite this there is also a little kick of satisfaction when an element in our own experience is common to the saintly person. Unfortunately that satisfaction only works when there is a corollary between those experiences. If Mother Teresa cared for the sick and I volunteer to help the homeless, I can share in the good of her deeds. However, if I don't do any charitable work at all the gravity of Mother Teresa's sacrifice functions as a source of guilt. On the other hand the feeling of powerlessness comes when we identify too closely with the person forced to make a sacrifice. It's very uncomfortable to know that some people are forced to make sacrifices against their will. It may be circumstances beyond their control or direct coercion. In either case, identifying with people in these circumstances highlights lack of control in our own circumstances, and thus the possibility of being forced to make significant sacrifices ourselves.

That's why the idea of the Splendid Doormat is so appealing. The doormat who asks nothing, who needs nothing, becomes alien. We don't identify with them because they are "so strong" or "so brave" that we strip them of their humanity and their frailty. These super-sacrifices cannot be hurt the way we can. Sacrifices we can't imagine occur daily for these saints. So we don't need to reconcile our experiences with these people. We never confront the idea that these people are just like us.

Because of this we can't unpack the idea of sacrifice without personal risk. We needn't make a personal sacrifice to begin the discussion. Beginning the discussion is a sacrifice of personal security. This discussion can start if we believe the risk is for something worthwhile. That is, after all, the fundamental nature of sacrifices. Dictionary.com provides several definitions that work well to kick off the conversation:

noun

1. the offering of animal, plant, or human life or of some material possession to a deity, as in propitiation or homage.

2. the person, animal, or thing so offered.

3. the surrender or destruction of something prized or desirable for the sake of something considered as having a higher or more pressing claim.

4. the thing so surrendered or devoted.

Right there in #3 we see it. The destruction of something prized for the sake of something with a more pressing claim. Applied to adoption this paints a very stark picture of what's going on for a first family. There's no sugar coating here. Something prized is being destroyed forever. Worth never enters this conversation. This is about needs, not wants or relative values. This is an experience most sane individuals don't want to get near. Jim Gritter covers circumstances of necessity well enough I won't go over it again here. But there's something else in the definition of sacrifice that muddies the waters.